Critique of Andrew Keen’s The cult of the amateur

Critique of Andrew Keen’s The cult of the amateur

Deciding upon the manner of my response to Mr Keen’s book required much, much more time than composing the response itself. It’s truly seductive to be scathing about the The Cult of the Amateur. Making an inventory of the book’s sloppy argumentation, its fallacious reasoning, its myopic stance, its uncritical praise of copyright, its unwitting foot soldiery of the entertainment industry, its selective choice of facts and its misquotations would be quite to the point – especially since Mr Keen accuses ‘today’s internet’ of being unwitting foot soldiers, sloppy, myopic, uncritical, selective, misrepresentative and fallacious.

But I’d rather not. Many of these points have been raised elsewhere, and rather convincingly so – by amateurs and professionals alike, I might add. Instead, my endeavour will be to come up with a series of points that I haven’t seen addressed elsewhere: the public and the private sphere, the press and impartiality, and commercials.

Keen argues that many blogs and most submissions on YouTube are trite. They are not artistic, they are not interesting, they are not worth anybody’s time. The net is gradually being filled with nonsense. Keen describes this development as narcissistic, and labels it the Cult of You: everybody is broadcasting themselves.

He’s actually right. There is an abundance of nonsense, of non-artistic clips, of badly written prose, of dreary streams of photographs. Some people argue that this is a necessary by-product of the open structure of the internet, and that we need to suffer this for a few pearls to surface. As Clay Shirkey wrote in his review of Keen’s book: ‘One of the many great things about the net is that talent can now express itself outside traditional frameworks; this extends to blogging, of course, but also to music, [..] or to software [..] and so on. The price of this, however, is that the amount of poorly written or produced material has expanded a million-fold. Increased failure is an inevitable byproduct of increased experimentation.’

To which Keen counters: ‘In the same way that not everyone should be doctors or teachers or astronauts, not everyone should be an author. Most people do not have anything interesting to say.’

What both Keen and Shirkey disregard, is that we are witnessing the private going public. People increasingly use the internet to capture, comment upon and share their lives. And while I’m not always sure what to make of that, in itself there’s nothing new about the phenomenon, only about its scale. People have always kept diaries, wrote updates for their friends and family, made snapshots documenting their life. The manner in which they did so changed whenever technologies changed, but the urge to share has always been present. It is ridiculous to demand that people in general should shut up, as Keen does, even though sometimes the urge to share is really annoying.

My parents’ generation poignantly remembers those long evenings during which they were forced to watch reels of slides of their friends’ vacations; they remember groping desperately for polite comments to make while inwardly growing more bored with every passing picture. And I vividly remember the shock, when I was sixteen and paid my second or third visit to our new neighbours, upon being made to watch a video of Mrs Neighbour giving birth to their kid while the couple sat next to me, proudly pointing out details that I tried to ignore. ‘See, that’s the placenta,’ they said, helpfully and happily, while I was trying not to vomit.

The good thing about this stuff being on the net is that you can easily click away when you happen to run into videos like this. The good thing about it being on the net is also that if you are interested what it entails to give birth, you can easily find videos like this and learn from them. Suddenly, witnessing somebody’s private life has become a choice, while before it was a social obligation.

The debate that Keen and Shirkey are conducting – whether these public expressions of private lives could carry some pearls, or it’s just a bunch of narcissistic monkeys hammering on their typepads – is simply misplaced. You don’t judge the drawings that your kid makes you by aesthetic criteria. The missive to family and friends that serves to update them about your vacation or your cancer treatment is not meant to compete for a Pulitzer, and should not be judged by its newsworthiness. The pictures of your new house are just that: pictures of your new house, and not intended to be of interest to others. What is interesting – and that question merits a discussion of its own – is why people nowadays find it so easy, nay: so self-evident, so natural, to publish details of their life for all to see.

One explanation is that people increasingly use their own private material (pictures, videos, blogs) as a means to find the like-minded. To find people who share their taste in politics, film, music, food, clothes, gardening, travelling, wine, cars, books; or to find people who are going through similar life events. People use one another’s private life to connect and to learn. In those cases, they are actually exploring the social fabric – and sometimes political dimensions – of their life. Indeed, that can only happen through a public process, which in turn makes a public place a logical and legitimate choice. A second explanation, and a slightly more pessimistic one, is that we simply have not managed to wrap our minds around the notion exactly how huge and how public the internet really is. We’re not yet used to thinking on such a grand scale; there is no precedent. Public places are often perceived as private or semi-private: my blog, our forum, our neighbourhood café. But gradually, social network sites are adjusting and are adding tools that allow users to define layers of intimacy: outsiders see hardly anything, acquaintances a bit more, and only to friends all is revealed.

But you can’t demand that people just shut up unless they have something interesting to say. That’s tantamount to robbing them of the narrative of their own life.

Next, Keen argues that all these people broadcasting about themselves represents the fragmentation of our culture, and that we need experts and gatekeepers to show us what’s worthy, valuable, and true and what is not. I would argue that insisting on a uniformed or codified point of view is not only patronising, but worse: it kills culture. Culture is never stable, nor is it something to be handed down by the few to the many. Culture is born of the clash of tradition and change, it grows and expands through public narratives and social conflicts, it is shaped by comments and clashes, and once it’s stable and preserved, it dies of undernourishment and poverty.

In some ways, The Cult of the Amateur reminded me of Allen Bloom’s book The Closing of the American Mind. In that 1987 bestseller, Bloom argued that pop culture was erasing high culture and that the effort of women and black people to have the literary and historical canon revised to include some of their experiences and milestones, was tantamount to dethroning good taste. But while Bloom saw social change as a war he was losing and chose sides, Keen regally disregards that there are, indeed, sides. In other words: Keen completely ignores the politics of culture and perceives culture as a monolith. What he calls fragmentation, I call social diversity. What he calls fragmentation, I call political argument. What he calls codification, I call cultural ostracizing and the smothering of dissent and diversity. What he calls trite, I call the fabric of other people’s daily life.

On to the second point: the press and impartiality. Keen holds the press in high esteem and applauds them as knowledgeable authorities with trained journalists in their employ and fact checkers at hand, who make responsible choices and cover the whole gamut. Thus, they have become institutes that have gained enough respect to get some special treatment: they are granted interviews with the high & mighty, they have their sources, they are granted impunity; all of which in turn improves their reporting.

Again, Keen is absolutely right. However, he’s only right for a tiny part of the press and television news, and thus, he presents us with a highly idealised and romanticised description of the press. Many newspapers and news shows are simply sloppy, copy or parrot one another, broadcast stuff that is just short of being gossip, consider news as an impure commodity (no longer good if touched by anybody else), are not impartial by a long stretch, publish press releases or syndicate news without any research, care less about truth than about sales, care more about sensationalism than about backgrounds or aftermaths, dress up ads as ‘infomercials’ or ‘advertorials’, and consider tidbits about an actor divorcing (or maybe not) to be prime news. (Even respected newspapers occasionally fall for hypes, as we have recently seen in the Netherlands with all the Fitna bruha.) In short, many newspapers and news programs behave exactly as Keen claims that only bloggers do.

Furthermore, his view of the press is unforgivably Western. With glee, Keen quotes a newspaper editor who states that the difference between newspapers and bloggers is that journalists , other than bloggers, are prepared to go to court – or to jail – for what they write. Never mind that quite a number of bloggers have been sued in Western countries for the news that they published and that Keen chooses to completely disregard them. (I do suggest however that he could do with a subscription to the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s news feed and familiarise himself with my own ten-year lawsuit.) With his outspoken approval of that editor’s statement, Keen shows a severe lack of understanding of the press and of the internet in struggling countries. In many Central European, North-African, Middle-East, Asian and South-American countries, newspapers are in cahoots with the government. If they weren’t, they couldn’t publish at all, and as it is, they are severely curtailed. In those countries is it bloggers who courageously escape censorship and find means to publish real news, and who often find themselves being persecuted or jailed, and sometimes worse, on account of that. Reporters Without Borders publish a yearly tally, and it’s a very uncomfortable picture that they paint: blogging can be fatal. Yet, even then – or perhaps especially then – people blog. Because they care enough about their country’s condition to tell the truth – albeit another kind of truth than the one that their governments cares to hear.

Next, Keen describes how newspapers are losing subscriptions and advertisements. Again, it’s the internet’s fault, according to Keen. Craigslist and Google now attract all the ads, and readers cancel their subscription because they can find the news on the net anyway, and hence have grown to believe that the news is or should be ‘free’.

However, newspapers have been going down in circulation ever since the 1980’s, and for the bigger part, they lost their readership to television. At the time, newspapers tackled the problem by focusing on their ad revenues – to the point where they created specialised supplements and weekend magazines in order to garnish more commercial space – and by devoting pages to more frivolous subjects such as life-style-news, in the hopes of regaining some readers. That is to say: newspapers countered their crisis by becoming less newsy and by moving away from their core business.

Keen also conveniently forgets that commercial television has cannibalised public channels. He ignores that some newspapers have been heavily subsidised by their owners not for the love of quality news but in order to kill off a competing paper and thus to get a bigger piece of the market. He fails to mention how newspapers that were loved by their readers were robbed of their identity because their owner ‘reshuffled’ some titles. He disregards that groups of newspapers have been bought and resold by venture capitalists looking for a quick buck, leaving the papers bleeding – as happened in the Netherlands.

In other words: their crisis has a longer standing and is much wider than Keen cares to admit, and its roots far precede the advent of the internet. And while Keen is rightly worried over the newspapers’ dwindling circulation in as far as it equates the downfall of investigative journalism, he fails to see that alas, that pitfall has perhaps more to do with the rise of commercial television and its perceived ‘free’ dissipation of news than with the rise of the internet or of Web 2.0.

We might want to discuss ads here. Keen regards commercials as the breath of life of the press, radio and television. But the main reason that I have completely given up on radio and almost stopped watching television is that I can no longer stand the barrage of ads. In newspapers, you can just flip the page or toss out the supplement, but in broadcasting media, you can’t. You have to suffer them. Everything that you’re trying listen to or watch and immerse yourself in, is being poisoned by yelling people trying to sell you something that you don’t want or need. By and large, it feels like broadcasting media are using content as a mere wrapping for ads.

I’m not the only one who is quite fed up. Hence the immense popularity of TiVo for television and of ad blockers in web browsers, and I am quite sure that some people’s habit of downloading episodes of series (whether on BitTorrent or on iTunes) or of waiting for the DVD release, can at least be partially explained by the fact that in these formats, the program comes ad-free. Oh, the relief. No ads. Unhampered content. At last. Mr Keen, making money by selling ad space is not a media-saving strategy. It is its nemesis. (It’s helpful to note that in the Netherlands, box office numbers rose after cinemas dropped the ads.)

If the printed press wants to reconsider its role and place – and I certainly hope that it will – it should place more weight on its content and its readership, less on ads. And while we’re at it: if they move to the internet, which many in the end will to do, they can cut on printing and distribution costs, thereby freeing a considerable part of their budget. Money that can be used to pay journalists and editors with. Yes, parts of the newspaper industry will suffer and people will lose their jobs – from paper producers and printers to newspaper delivery boys.

But we don’t lament the implementation of printing technology because it put scribes out of work. We did however decry the implied loss of authority: suddenly, everybody could read what the bible said and form their own opinion about its content, instead of having to patiently wait for the priest to give his selection, his interpretation, his guidance and his verdict. Printing created the wish to become literate; literacy created choice and dissent. And I’m quite sure that when the first novels were printed, some people complained that this was not what we had invented that wonderful technology for.

Yes, we are losing gatekeepers. We actually have been doing so for centuries. Almost invariably, that was a terribly useful and liberating development. Indeed, sometimes – but usually for brief periods only – we were confused, at times frighteningly so. These changes have certainly not always been uniformly positive, but unlike Keen, I don’t think for one second that any technology has made us dumber per se or has robbed us of our culture. We tend to turn any and all communication technology into a means of cultural production, with or without our being paid to do so, and Keens self-professed nostalgia is just that: a bad case of nostalgia.

[In de Volkskrant verscheen een Nederlandse samenvatting van deze lezing, een beetje staccato want met meer dan de helft bekort.]

Verscholen in onze dromen zit de technologie van onze tijd. Zelden zul je midden in de nacht in een paardenkoets stappen of met een tondeldoos vuur maken, terwijl onze opa’s en oma’s dat vast nog geregeld deden. In je slaap een koelkast hebben die zelfstandig de boodschappen afhandelt, is al evenzeer uitzondering en waarschijnlijk pas regel in de dromen van ons nageslacht. Maar iemand opbellen of de tv aanzetten in een droom is tegenwoordig heel gewoon, dat is na het ontwaken niet iets dat je raar of opmerkelijk vindt.

Verscholen in onze dromen zit de technologie van onze tijd. Zelden zul je midden in de nacht in een paardenkoets stappen of met een tondeldoos vuur maken, terwijl onze opa’s en oma’s dat vast nog geregeld deden. In je slaap een koelkast hebben die zelfstandig de boodschappen afhandelt, is al evenzeer uitzondering en waarschijnlijk pas regel in de dromen van ons nageslacht. Maar iemand opbellen of de tv aanzetten in een droom is tegenwoordig heel gewoon, dat is na het ontwaken niet iets dat je raar of opmerkelijk vindt. Afgelopen weekend deed

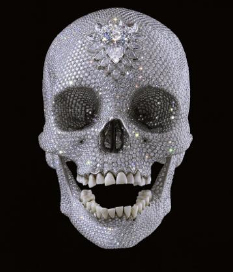

Afgelopen weekend deed  De met 8601 diamanten ingelegde platina schedel die Damien Hirst heeft gemaakt – het werk heet ‘For the love of God’ en zou iets moeten zeggen over onze sterfelijkheid – is vanaf overmorgen (1 november) tot half december te bezichtigen in het

De met 8601 diamanten ingelegde platina schedel die Damien Hirst heeft gemaakt – het werk heet ‘For the love of God’ en zou iets moeten zeggen over onze sterfelijkheid – is vanaf overmorgen (1 november) tot half december te bezichtigen in het

Lenore Skenazy, een Amerikaanse vrouw met een zoontje van negen, schreef afgelopen week een artikel in de New York Sun over een tochtje dat haar zoon door de stad had gemaakt. Haar kind had al tijdenlang gesmeekt of-ie niet eens alleen naar huis mocht, hij was immers al groot genoeg, vond-ie. Skenazy stemde uiteindelijk in: ze gaf hem een strippenkaart mee, een plattegrond van de metro en een briefje van twintig dollar plus wat munten voor de telefoon.

Lenore Skenazy, een Amerikaanse vrouw met een zoontje van negen, schreef afgelopen week een artikel in de New York Sun over een tochtje dat haar zoon door de stad had gemaakt. Haar kind had al tijdenlang gesmeekt of-ie niet eens alleen naar huis mocht, hij was immers al groot genoeg, vond-ie. Skenazy stemde uiteindelijk in: ze gaf hem een strippenkaart mee, een plattegrond van de metro en een briefje van twintig dollar plus wat munten voor de telefoon. Bespreking van Andrew Keens The cult of the amateur

Bespreking van Andrew Keens The cult of the amateur

Wanneer het begon herinner ik me niet meer – het zal zich geleidelijk hebben ontwikkeld, eerst nauwelijks merkbaar en nu zo opvallend dat ik het zelf eindelijk doorheb – maar tegenwoordig zeg ik meestal ‘u’ tegen mensen die ik eerder vrijwel zeker zou hebben getutoyeerd., en in dezelfde beweging ‘je’ tegen mensen die ik vroeger met ‘u’ zou hebben aangesproken.

Wanneer het begon herinner ik me niet meer – het zal zich geleidelijk hebben ontwikkeld, eerst nauwelijks merkbaar en nu zo opvallend dat ik het zelf eindelijk doorheb – maar tegenwoordig zeg ik meestal ‘u’ tegen mensen die ik eerder vrijwel zeker zou hebben getutoyeerd., en in dezelfde beweging ‘je’ tegen mensen die ik vroeger met ‘u’ zou hebben aangesproken. Details:

Details: Mijn ogen lichtten afgelopen week op, daar op

Mijn ogen lichtten afgelopen week op, daar op  De werkelijke gevaren van technologie liggen elders. Dat was diezelfde week elders al even tastbaar, bij de uitreikingen van de

De werkelijke gevaren van technologie liggen elders. Dat was diezelfde week elders al even tastbaar, bij de uitreikingen van de