And again, I find the Pink Ribbon campaign infuriating. Last year, after I had become acquainted with breast cancer firsthand, the campaign made me feel like a baby seal: I was treated as a cuddly doe-eyed pet that anybody who was half famous expressed their heartfelt concerns about, but who wasn’t allowed to utter a word herself. It was a glamour campaign from which stories about amputations, chemo, radiotherapy, forced menopause and – yuk! – loss, fear and death were skillfully erased. Such realistic stories might frighten other women, and then they wouldn’t buy the magazine. An honest campaign would be counterproductive. Said Pink Ribbon.

And again, I find the Pink Ribbon campaign infuriating. Last year, after I had become acquainted with breast cancer firsthand, the campaign made me feel like a baby seal: I was treated as a cuddly doe-eyed pet that anybody who was half famous expressed their heartfelt concerns about, but who wasn’t allowed to utter a word herself. It was a glamour campaign from which stories about amputations, chemo, radiotherapy, forced menopause and – yuk! – loss, fear and death were skillfully erased. Such realistic stories might frighten other women, and then they wouldn’t buy the magazine. An honest campaign would be counterproductive. Said Pink Ribbon.

This campaign is demeaning and portrays us as infantile. Women with pink umbrellas, women with pink glitters, women with pink lady-phones: it is as we’re thrown back into being twelve years old, with braids and bows, unable to see further than the end of our Barbie’s nose. Is there any other campaign about any serious illnesses in which the target group is addressed so fluffily and so veiled? Does Pink Ribbon really believe that women can’t face the truth unless it’s wrapped in pastel pink? Does the organization honestly think that women have to be addressed as if they’re slightly retarded?

The tone of this year’s campaign has slightly improved, but the conspicuous consumerism – I wrote about that last year – seems only to have intensified. Companies donate a mere fraction of their revenues, donations which are tax deductible at that, and through our commitment to ‘the cause’ they manage to acquire themselves a shiny, engaged image. Fight breast cancer, buy a pink vacuum cleaner! Fight breast cancer, buy a Samsung Lady phone! Fight cancer, buy! Be a hero, buy our stuff! The campaign is providing a plenary indulgence for the consumer. Buy, and get yourself an instant halo!

‘If shopping could cure breast cancer, it would be cured by now,’ says Think before you Pink on its web site – a scathing but painfully justified remark. Think before you Pink (TBYP) furthermore points out that Pink Ribbon does not show any records of its incomes and spendings. In the Netherlands, various journalists and other interested parties have asked for accountancy reports, but they have received no reply. What do these campaigns really garnish, except for an ‘socially engaged’ image for companies such as Samsung, Estée Lauder and KPN, and a few photo opportunities for semi-celebrities? Where and how is the money actually spent? How much money is used for the actual prevention and curing of breast cancer?

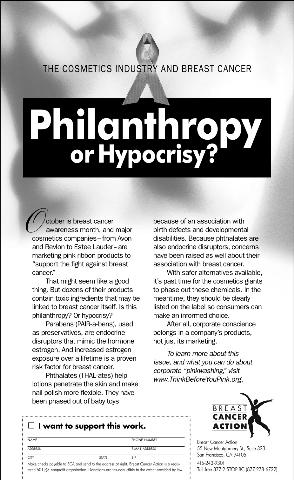

TBYP does more than posing nasty questions: they delve up nasty facts. A number of companies use the Pink Ribbon campaign to clean their image (but not their act). TYBP refers to that as pinkwashing. For instance: Pink Ribbon was started by the cosmetics company Estée Lauder, which has ever since managed to get quite some good press out of their involvement.

TBYP does more than posing nasty questions: they delve up nasty facts. A number of companies use the Pink Ribbon campaign to clean their image (but not their act). TYBP refers to that as pinkwashing. For instance: Pink Ribbon was started by the cosmetics company Estée Lauder, which has ever since managed to get quite some good press out of their involvement.

But there is another campaign that Estée Lauder refuses to support, to wit: the Campaign for Safe Cosmetics. Three hundred companies have signed that campaign, but Estée Lauder, L’Oreal and Proctor & Gamble are not amongst them. In 2003, the European Commision forced these companies to drop the use of phthalates – a chemical substance that strengthens nail varnish – because they’re toxic and hormonal disruptive, and have been labeled as carcinogenic.

Isn’t that twisted? A company that uses carcinogenic ingredients and that has to be called to task by the EU, is posing as the biggest campaigner against breast cancer. Estée Lauder has also been named in a few cases of dumping chemical waste.

Indeed. Think before you Pink. Please.

(Translation of one of my Parool columns. Het Parool is a Dutch newspaper, in which I have a biweekly column.)